Barnhart speaks out on restarts, penalties

Interviews, Podcasts — By More Front Wing Staff on April 27, 2011 6:51 pmTo hear the entire audio interview, click on the player below or search for ‘More Front Wing’ on iTunes.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Earlier today, INDYCAR President of Competition and Racing Operations Brian Barnhart spoke with More Front Wing on the subject of Race Control and the officiating concerns raised after the event at Long Beach.

Operations in Race Control. Before getting into the finer details specific to Long Beach, we asked Barnhart to explain the environment in Race Control during an event. “It’s a bit of a challenge simply because it is a fairly unique sport in that we don’t have time-outs, we don’t have the ability to stop the competition and review and replay something like the NFL does, or Major League Baseball reviewing home runs, and stuff like that. Our event is on the fly all the time, and decisions need to be made in a timely fashion. It is a challenging environment in there and varies from venue to venue. Doing road and street events is considerably different than doing oval track events. At most of the oval track events, Race Control is on the outside of the racetrack right at the start/finish line and you can see the entire racetrack. At most of the road and street events, I can’t even see any segment of the racetrack. At Long Beach, we actually do it from a locker room in the Long Beach Arena, and we are totally dependent on what television cameras are showing us. Now, that becomes a bit of a challenge because they don’t always show us what we would like to see or what is the action point around the racetrack for a variety of reasons, whether the cameraman chooses to follow a different car or whatnot.”

Barnhart went on to describe the environment in Race Control at a road course and give more detail on the roles of the personnel. “We’ve got multiple video screens in there on several television sets that show us on road courses upwards of 12 to 16 camera views, depending on the number of corners, number of cameras. Bill van de Sandt and Tony Cotman specifically monitor our digital video recording equipment, which includes those cameras as well as the on-board cameras of the cars that are carrying cameras at that event. Al Unser, Jr. and I focus on the screens that are carrying the event live. He have Jim Swintal as our voice on Race Control, and he relays the commands to all the pit techs, the teams, the pace car driver, the starter, the flagman, all that stuff. Jim Norman is our fire control, and he’s talking to the wreckers, the ambulances, the track safety guys and clean-up trucks, sweepers, that kind of stuff. Dave Price is our main communicator with our corner worker network and observer network, talking to our network of people around the racetrack that are relaying information back on the land line or radio back to him with regards to track and car conditions.”

Barnhart also offered clarification on whether all four of the personnel in Race Control have equal say in officiating decisions. “Ultimately, the decision is mine,” Barnhart replied, “but they all have equal ability to weigh in and, certainly, give their opinions. If I find myself in a position with simply too many things taking place at the same time, it’s not uncommon for me to turn to any of the other three and say, ‘Guys, take a look at that and let me know what you think.’ And I have the trust and faith in them to make those decisions and determinations.”

Avoidable contact. When the subject turned to avoidable contact penalties, Barnhart took the lead in the discussion. “I think it’s important as well for people to get a better understanding of what the rules are, what the interpretations are, what the expectations are, and then what the penalties are because I think when you have a full understanding of that — at least, in my opinion, of course it would be my opinion — Race Control has been extremely fair and extremely consistent with our enforcement of the rules all year long. And I think the important part is that if you have a driver that is trying to improve his or her position on the racetrack and in doing so attempts to make a pass in an illegal, unsafe, careless or reckless fashion, or an unsportsmanlike maneuver that results in contact with another car, that’s when we will initiate a review to see if it was avoidable contact, to see if this person advantaged their position in the race in an unsportsmanlike maneuver, and that’s what we’re looking for.”

Barnhart went on to provide greater detail on the incidents that have been under review thus far in the 2011 season and what the penalty is for an instance of avoidable contact. “We’ve had six incidents that Race Control has seen or tried to review and rule on whether there was avoidable contact or not. Once you make that determination, the other important aspect is to remember what the penalty is for consistent enforcement. If the track condition is green, the penalty is a drive-through penalty through the pits at the pit lane speed limit. If we’ve gone full-course caution as a result of the contact, the instigating or offending driver is moved to the back of the field.

“If you go back and look at those six incidents, the first one starts with Helio in turn 1 of lap 1 at St. Pete and the multi-car accident initiated by Helio and his contact with Marco. We go full-course caution, obviously, so the penalty would be Helio at the back of the line. Well, there’s no ability to enforce that penalty. His car’s on the wrecker. It goes back to the tent and he spends 20 to 25 laps in the garage area effecting repairs on his car while the race resumed without him. He has, in effect, penalized himself worse than what the Race Control penalty would be.

INDYCAR Race Control deemed Castroneves loss of laps sufficient penalty for the early melee at St. Pete

“Later in the race, you had Danica running 12th and JR Hildebrand running 11th. On the last lap of the race, they were the last two cars on the lead lap and the 13th place car was two laps behind them. Going into turn 10, Danica roots around Hildebrand, turns him around in turn 10 with her nose onto his left rear. The checkered flag comes out, so there’s no opportunity for us to do a drive-through penalty. So, the only penalty can be the equivalent of putting her at the back of the line as it finishes, which gives Hildebrand back the position of 11th, moves her back to 12th, but does not move her back any further than that because the 13th place car and on down were two or more laps behind her. But again, it was consistent with the ruling and the placement of her in the field.

“You go to Barber, and Hunter-Reay and Briscoe get together in turn 8 battling for third place. Hunter-Reay continues. Briscoe has broken suspension and ends up in the sand trap. We go full-course caution to dig him out. His event is concluded. And clearly, Hunter-Reay’s attempting to make a pass and [the incident] in our opinion was ruled avoidable contact. We’re under a full-course caution, that ruling is made, and Hunter-Reay goes to the back of the line, again consistent with what we’re doing.

“You move on to Long Beach and the situation with Castroneves and Wilson in turn 11. Again, people have got to look at and understand what the rules are, and the rule for avoidable contact is if a driver is attempting to improve his or her position or attempting to overtake another car in an unsafe fashion or an unsportsmanlike fashion. Helio was not attempting to pass. They were running nose to tail. He was following Wilson through the corner. He did not make a dive-bomb attempt into turn 11 to try and pass him. In addition to that, upon review, Justin’s on-board camera shows how much Justin was struggling with his car’s handling through turn 10, and when Al and Tony reviewed Justin’s on-board camera, you see him oversteering in turn 10 two or three times and on and off the throttle. And with Helio in that close proximity behind him with his nose tucked right up underneath his gearbox, they touched, made contact, and spun him around. But in Race Control’s determination, it was not a careless, reckless maneuver and not an overtaking attempt. It was ruled just a racing incident of contact, so no penalty was called for.

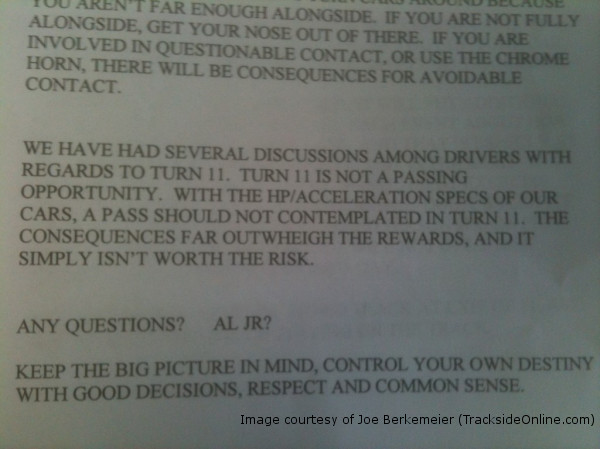

“Now, just a few laps later, you look at Tracy’s situation. I know that the fans and the media aren’t always in the drivers’ meetings, but in the drivers’ meeting we talked about turn 11 and told them, ‘Guys, 999 out of 1000 pass attempts in turn 11 will result in contact. It is not a place you even want to try an overtaking or a passing attempt. Don’t do it. You will just risk contact and get somebody turned around. It’s not a passing zone on the racetrack. Use your head in turn 11.’ Tracy was attempting to pass a car in turn 11, overshot that car, made contact with Simona, turned her around. By very definition, attempting to improve his position in a careless and reckless and unsafe and unsportsmanlike fashion, he makes contact with another car. Result: full-course caution. He’s moved to the back of the line, just like Hunter-Reay was, just like Danica was, and just like Helio would have been previously. So, again, we’re totally consistent.

“Later in the race, when Helio gets into Power running for third going down into turn 1 and spins both of them out, they both stall. Again, we go full-course caution, and by the time we restarted both cars, they were both at the back of the line. Now, a determination for Helio to be the instigator and cause of avoidable contact, the penalty would put him at the back of the field. He was at the back of the field by the time we restarted him and sent him around. Race Control at that time doesn’t make an announcement and say ‘3 car, back of the line.’ You look like an idiot. He’s already back there. So, again, when you look at the contact and situations we have, the determination and the interpretation, the offending car has ended up in the exact same place in all five instances. It has been at the back of the line or in the garage making repairs to their own damaged car.”

At the end of his detailed explanation, Barnhart summarizes his motivation for laying everything out: “It really kind of boggles my mind how people see it that way [that Race Control is being inconsistent].”

When asked whether Race Control has considered issuing a penalty to create a public record even in situations where it would have no effect on track position, Barnhart replies, “I think that’s highly redundant, to be honest with you. Like I say, knowing what the penalties are for avoidable contact and that the resulting car ends up there, there’s so much going on in Race Control, I don’t think we need to waste our breath or say something that is so painfully obvious and redundant like ‘3 car’s been penalized, go to the back of the line.’ When you say that and he’s already there, it makes you look foolish.”

Barnhart also commented on whether a driver’s history or reputation might play into Race Control’s decision-making. “I don’t know,” he started. “If it does, there may be subconscious coming into it. Some people have a different reputation, obviously, than others. To be honest with you, over the course of time I think some of them earn a shorter leash than others based on their actions on the racetrack. If they have a history, if they’re prone to contact and overly aggressive driving, you tend to maybe be a little shorter with the leash on them and more quick to make a determination than someone that hasn’t had contact with somebody in three years and they happen to have one. You know it’s not a driving pattern or a typical behavior demonstration or pattern that they put on the racetrack. So, you do your best to look at each individual incident as it happens, but I’m sure there’s some of it in the back of your mind that sits there and says, boy, this guy’s been involved in seven incidents already this year and blah, blah, blah, that kind of stuff. So, you can get into that pattern, for sure.”

Passing in turn 11. When asked whether turn 11 at Long Beach was officially designated a no-passing zone, Barnhart began by offering some background. “We’ve had discussions prior to the event. Some of the drivers request that turn 11 be a standing yellow every lap of every session, including the race, because they don’t want drivers to attempt to pass. Again — and I know we don’t get much credit for actually thinking things through, but believe it or not, we really do — the challenge with that is, as I’ve told the drivers, how are we going to mark this? If we agree and we make this a no-passing zone, if we’re going to actually hang a standing yellow, then you’ve got to have a line where that zone begins. If somebody’s coming through turn 10 and attempting a pass, then you have to have a point where that pass has to be completed by or they have to move back behind them. And in addition to that, and as I’ve asked these drivers, you literally want the corner worker to stand there and hang a yellow flag out every lap? Well, when somebody comes around that corner and spins sideways and you’re the next car on the scene and that guy’s waving that yellow flag, are you thinking he’s just waving that yellow flag because it’s a no-passing zone? How are you going to know the difference? There’s actually a disabled car and an unsafe condition in front of you. So, there’s a number of reasons why we haven’t officially made turn 11 a no-passing zone, but we’ve made it clear in each of the last couple, three years there, ‘Guys, you are just not making a good decision.’ The tightest, slowest, most difficult, challenging part of the racetrack to attempt to pass is followed by the longest straightaway and the best passing zone on the racetrack. If you will just stay tucked in behind him and take your chances down a 2,900 foot front straightaway with a heavy braking into turn 1, you have a much better chance there than you do at turn 11. It just simply boils down to these guys have got to make good decisions in the race car.”

So, the recommendation not to pass in turn 11 at Long Beach was something that was actually requested by the drivers? Barnhart replies, “Absolutely.”

Restarts. Barnhart addresses whether the start and restarts at Long Beach were considered acceptable by Race Control. “It’s again one of those really challenging racetracks to get guys around the corner,” he begins. “We took an awful lot of time on Thursday and Friday in dealing with the driver advisory group on where the line should be for acceleration. I thought we did a much better job at Barber than we did at St. Pete on the formation, the form-up, the speed, the spacing, the gaps, all that kind of stuff. But I think, unfortunately, a huge contributor to the improvement at Barber over St. Pete was the track geometry. And conversely, the track geometry at Long Beach, that hairpin, turn 11, is simply a single-file corner no matter what we do. And when you come off of that corner, you’ve only got about 800 feet prior to the start-finish line, and when they’re single-file, it doesn’t give them much time to jump out of that corner and form up. In fact, we had even tried to split the difference with there the line was and the acceleration point.

“The initial start was even worse than I had thought or hoped it was going to be. However, again, you don’t have a lot of television views that show us everything that we’re looking for all the way back. They focus on a handful of cars. The start wasn’t real good, so the reaction that we made, we took the pace car off into the back door at turn 10 on the initial start of the race. After seeing what the start looked like and trying to improve the restarts, slowing the front of the field down and trying to improve the ability to get more rows lined up, we kept the pace car out for all restarts all the way through turn 11 and brought him in the front door pit opening, just as all cars pitted. It was marginal, the difference that it made. It’s so difficult to get guys around the corner in there and get them lined up in the double-file formation. The challenging aspect of it, with turn 1 being what it is down in Long Beach, there was a lot of agreement amongst the drivers that if there was an issue in terms of where it looked worse, they would rather look worse coming out of 11 than have it look bad in turn 1 where we would have a stack-up or a red flag situation because we’ve blocked the track with a big crash down there.

Given the challenges that Long Beach was clearly going to present, was any consideration given to moving the start/finish line to give the cars more time to line up? “There’s a lot of dominoes that get knocked over in doing that. There’s a lot of people that pay money in those suites and those front grandstand tickets to watch the start of the race. That’s part of the reason you start Mid-Ohio in the back is that’s where all the fans are and they want to see it down there. It isn’t just from a safety or a location standpoint. You restart under the bridge down the back between 8 and 9 at Long Beach, nobody’s going to see it. So, I don’t think that’s fair to the fans to do it that way as well. In terms of moving the start/finish line, again, that’s not easy. When you’re dealing with city streets, if you’re going to move start/finish lines, we’ve got to cut up a lot of racetrack and replace time lines that help us know where drivers have improved positions or not, and getting cooperation and closing city streets to install time lines is not an easy thing to do, and it’s a very time-consuming, expensive thing to do just to move it for that aspect of it.”

Barnhart also addressed why the start and restarts haven’t been waved off if the field is not in formation. “That’s one of the by-products of the change that’s been implemented and what we’re doing, and based on the feedback from the teams and the drivers, they’ve virtually come to a unanimous conclusion that, in the interest of safety with us being double-file and how we’re doing these restarts now, that we will go each and every time. We will not wave off any starts.

“What we will do is penalize someone who has either changed lanes or improved their position prior to the start/finish line. So, there isn’t much consideration given anymore to waving off. What we’re looking for is to see if people have changed lanes prior to the start/finish line and gotten out of formation or if they’ve improved their position relative to a car in a row in front of them prior to the start/finish line. We don’t look too much within individual rows. We need the leader to make sure he hits start/finish line before the other car on the front row, but everybody else, if you’re in the fifth row, I don’t really care if 10th is in front of 9th or 9th is in front of 10th. I need to make sure the leader hits the start/finish line first. All the other rows can be plus one or minus one relative to cars within their row. You cannot improve your position relative to any car in a row in front of you.”

Looking forward, Barnhart acknowledges that Brazil will present similar challenges. “We’ve got another hairpin down there. I think they can go two-wide around that hairpin. It’s wide enough to do it, and the straightaway’s longer. The challenge is going to be turn 1 at Brazil is a very slow and tricky corner. The only attempt at double-file start was the initial start last year, and we ended up with somebody on some guy’s head, so it’s a tricky situation down there as well.”

Tags: Brian Barnhart, Verizon IndyCar Series - Administration

I only got one problem with everything he said here:

———-

When asked whether Race Control has considered issuing a penalty to create a public record even in situations where it would have no effect on track position, Barnhart replies, “I think that’s highly redundant, to be honest with you. Like I say, knowing what the penalties are for avoidable contact and that the resulting car ends up there, there’s so much going on in Race Control, I don’t think we need to waste our breath or say something that is so painfully obvious and redundant like ’3 car’s been penalized, go to the back of the line.’ When you say that and he’s already there, it makes you look foolish.”

———-

Am I to believe that his royal highness can’t understand that it was the failure to announce penalties that caused this whole flap-doodle in the first place? And even after all the negative BS that has come down on his head, he still can’t see why announcing and infraction, even if the penalty is redundant, would be very, very good idea?

I find that pretty hard to swallow. What is this dude’s trip? He thinks that announcing an infraction without assessing a penalty would make him look foolish?

That never stops ’em in the NFL. And reason it doesn’t stop them is because they have thrown a flag, so they then have to explain it whether there is a penalty or not.

Race Control is NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS. Brian Barnhart will tell you what you need to know. If he doesn’t think you need to know, then he won’t say anything.

If you complain about that, you are stupid, because announcing anything about those particular infractions would be “redundant,” which is stupid. Brian Barnhart just called anybody that disagrees with him about the way he runs Race Control, stupid.

What a dick. I never thought this guy should be fired before, but I think I just changed my mind.

I’m not sure I buy his explanation on the avoidable contact calls. But if they are making calls based on video, they should be able to make that video available on-line after the race (if not during the race telecast) so fans can see the contact that led to the penalty. Of the three assessed penalties (Danica, RHR, and PT) on only one of them have we seen the actual contact (RHR).

Personally, I don’t really care one way or the other about Barnhart but really disappointed in the answers on the double-file restarts. It is like Race Control has given up trying to administer the double-file restarts…based on what he said they are never going to penalize anyone for jumping the start unless it is the front-row. I’m all for having a Driver’s Council that will give feedback on safety but they shouldn’t be allowed to tell race control how the starts will go, which is basically what is happening. If they aren’t going to wave off the starts they need to be aggressive in handing out penalties related to the start.

His response clearly shows he makes up the rules as he sees fit, and doesn’t even know what is in the official rule book. I was afraid of that after reading Al Jr’s lame excuse for a defense of what goes on in Race Control, and this only confirms what I’d hoped was not the case.

I challenge anybody to find a requirement in the official rules that avoidable contact must involve an attempt to pass or improve one’s own position to be subject to penalty…because there is absolutely ZERO basis for his comment, the rule book contains NO such provision!

Section 9.3.C of the 2011 rule book forbids avoidable contact that interrupts a competitor’s position or lap time…and does not state that the contact must be the result of a pass or an attempted to pass?

Where does he get this crap? Oh, we know all right, he gets it exactly where most crap comes from!!!

Uh… I don’t really know how to respond to this, yet. My first thought on reading this is that Barnhardt needs to be sacked, and any driver who really wanted a standing yellow every lap at turn 11 needs to find a new job. I cannot imagine what would happen if a NASCAR, MotoGP, WSBK, or F1 driver said that. Also, just because drivers and team owners want something doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. So what if they don’t like the idea of a waved off start??? If a start is bad, it get’s waved off. That’s how it’s done in a normal racing series.

And they’ll penalize you for contact from attempting to pass but not if you make contact while not trying to pass??? So they’re seriously encouraging drivers not to pass? That makes a world of sense… All I can say is for a series that is one of the premier forms of racing in the world, that’s pretty pathetic. If this is how the series is officiated… I’m scared for the future.

I thought it was a reasonable answer from him. However, I think they should probably at least document the infractions for posterity. At least it then has the appearance of fairness. The NFL example above is a good comparison. As far as the penalties, I think what he said about Helio and Wilson was fine. I’d like to have seen the video, but if I guy in front of you drives poorly and you hit him because of that guy’s difficulties, then how can you say there should be a penalty on the trailing driver? As far as turn 11 is concerned, they didn’t say you can’t pass, just that if you try it and you knock someone out of the way, you will get penalized. If you think you can make a banzai move and not hit someone or cause a yellow, as a driver, you have to weigh the risk/reward. Just be judicious about your passing.

Some of what BB said about penalties made some sense but the rules and the process seem inconsistent with international rules as seen in F1, ALMS and turing cars. That all by itself makes IndyCar look arbitrary and capricious which leads directly to my seconds observation. BB’s two contentions, first that they are, without deviation, always right and therefore no further explanation is necessary and second, that waving off restarts is not necessary because and I’m paraphrasing, “the drivers are on board” boils down to one conclusion. BB is god, his decisions are infallible and if the racing suffers, tough shit.

Good article….

Brian Barnhart’s comment that Helio was in effect penalized because he ended up at the end of the line is simply not true. At the next restart, Helio was second from the back; Will Power was at the back of the line.

From a Curt Cavin article at Indy.com: “…But there was some irony in the positioning of the cars for the next restart. ‘Oddly enough, (Castroneves) ended up in the back in front of me,’ Power said…”

I broke down this whole interview with Brian Barnhart (which was excellent, by the way, so kudos to you on the “get”, More Front Wingers) nearly line by line yesterday with a buddy of mine in e-mail form (I was having a bit of a slow afternoon), but I’ll spare everybody the 9,000 word breakdown, and sum up the best I can.

I am basically willing to concede that Helio’s incident with Wilson may have been a “racing incident”, that Justin suddenly slowed, and that Helio hit him entirely by mistake. Fine, whatever. Benefit of the doubt for Race Control on that one. It looks awful that PT got a penalty in the same corner for a similar incident, but sometimes that’s the way the cookie crumbles. PT is an idiot for trying to attempt a pass there (if that’s what happened), and if that passing attempt caused an accident that consisted of him hitting, spinning and parking another competitor, then by all means, PT gets a penalty. PT’s been driving at Long Beach for over 20 years, so he knows what the score is for the hairpin. This, mind you, does not mean that I think there should have been a standing yellow for Turn 11, and Barnhart was right to turn down the drivers on that (however, he was wrong for there to be an unspoken yellow for that corner; that’s something that you do only if the pavement is breaking up somewhere, like F1 did at Montreal a few years ago and ChampCar did, I think, at San Jose). If a driver has a 25 MPH advantage on another driver on the approach through Turn 10 and can make a pass happen with little to no contact and without wrecking or spinning the other car, then have at it. If you can make a clean pass, you can do it anywhere: straightaway, mid corner, corner exit, with two wheels on top of the wall, spinning backwards down the track Joe Tanto-style, whatever. Do it clean or 99% clean and it counts. However, if you hit another driver hard enough to spin them and you get away still on the lead lap, then you can expect a penalty for your poor judgment. I’m disappointed that Race Control can not find video to support the PT penalty (especially since the penalty was supposedly based on video evidence), but that’s the way that goes. Innocent until proven guilty, I guess.

Back to Helio and his late race accident. You can not, under any circumstances, allow what he did to Power (and, by extension, Servia and Dixon) to stand without at least making an attempt at enforcing a penalty. Failing to do so will only make you look biased, especially if 2 of the 3 guys in Race Control are former employees of the team in question. You can’t just say “well, Helio’s at the back of the line and Roger’s going to yell at him later. Done and done.” Your rulebook should be written something like “driver sent to the back of the line or any other penalty that Race Control deems fair” (aren’t rules for most sports written like this? Doesn’t even NASCAR, in their infinite stupidity, have the latitude to enforce whatever rule they want whenever they want?). Then, you can make Helio do a green flag troll down pit lane, and now his race for any position other than last car on the lead lap is over unless he catches another late race yellow. Or, you can bring him in and hold him for a lap, and now he’s guaranteed to only be racing with EJ Viso for the duration, and then, only if EJ hasn’t already destroyed most of his car. If you just let him re-join at the back with no penalty, well, guess what? Now he can assault another car at his leisure or improve his position as he could have before the incident. Yes, he’s at the back of the line, but he’s still in the middle of the race for position. This is unacceptable. If this aspect is down to the way the rule is written, then the rulebook needs to be re-written.

Brian Barnhart’s comments on never waving off a start or restart, however, are the absolute height of stupidity.

Barnhart: “What we will do is penalize someone who has either changed lanes or improved their position prior to the start/finish line. So, there isn’t much consideration given anymore to waving off.”

This sounds great, but it never happens. Ever. Somebody could check the recordbooks, but I can never remember such a thing being penalized, even when Helio’s gotten multiple carlength jumps at Indy the last two years.

Barnhart: “We don’t look too much within individual rows. We need the leader to make sure he hits start/finish line before the other car on the front row, but everybody else, if you’re in the fifth row, I don’t really care if 10th is in front of 9th or 9th is in front of 10th. I need to make sure the leader hits the start/finish line first. All the other rows can be plus one or minus one relative to cars within their row. You cannot improve your position relative to any car in a row in front of you.”

This also sounds great, but is also never enforced. Anybody who’s sat within 3 rows of me at Indy the last 3-4 years has heard me screaming about people jumping out of line and making 2-3 passes for position even before the apex of Turn 4, which is certainly before the green has come out. I say that once the green is out, we go racing. Before the green is out, we’re in alignment and going the same speed.

As for guys jumping the start, here’s an idea: if a guy jumps on the gas before the green comes out, do not throw the green and put that guy at the back. Jump starts will stop instantaneously, because people will rather lose potentially 1-2 spots on a bad start or restart instead of 20, in the case where they jump and get caught. Problem solved.

I am really sorry to write a book here (I should probably look up the URL of the website that I supposedly write for one of these days and write my own damn column), and I totally understand if I am the only one who made it all the way to this part of the text, but I am fired up. The Series has some great stuff going on, and fantastic racing, but I think that it’s going to have a hard time getting taken seriously by competitors, teams, sponsors, and most importantly, the fans, unless things get cleaned up in the Race Control booth. That needs to happen, like, before Memorial Day.

[…] Brian Barnhart told MFW a couple of months ago that he has no intention of waving off any restarts (http://morefrontwing.com/2011/04/27/barnhart-speaks-out/), and the way that things operated at start-finish made that abundantly clear. The drivers […]